If Robert Finley had been Noah – you know, the one called by God to build the Ark – he would have done things differently. “Many things don’t make sense, but it makes all the sense in the world,” he says, ever-the storyteller. “Even him building the Ark up on top of a mountain would’ve been crazy to me, because I would’ve built it down…where the water is.” As the Bible—and now Robert—describes, naysayers looked on, watching Noah complete this insane and impossible task. “But he did what God said he do,” Robert explains. Noah kept on, the rain came, so did the animals, two-by-two. “Dogs went back to chasing rabbits, probably when they got where they were going, but on the ship, the dog wasn’t running [after] the rabbit, the dog wouldn’t fight with the cat. The cat wasn’t trying to eat the rat. Everything got along.” Robert figures, with everything so harmonious, Noah must have had some music on that boat.

Now 69 years old, Robert himself knows a thing or two about conquering the impossible—and keeping the faith. The last time we spoke was on the verge of the May 2021 release of Sharecropper’s Son, his autobiographical, funky country-soul album, its musical stories inspired by his early life in rural Louisiana, one of eight children who grew up picking cotton as soon as he was old enough to walk. An Army veteran and skilled carpenter, it wasn’t until he lost his eyesight in his 60s that Robert devoted his life fully to his music, a passion that began as a boy when he purchased a guitar with money his father gave him for new shoes.

Also Read

Robert Finley Announces U.S. Winter Tour

His June 2021 cover story was a first for both of us here at SPIN. Sharecropper’s Son was one of the most lauded releases of 2021.

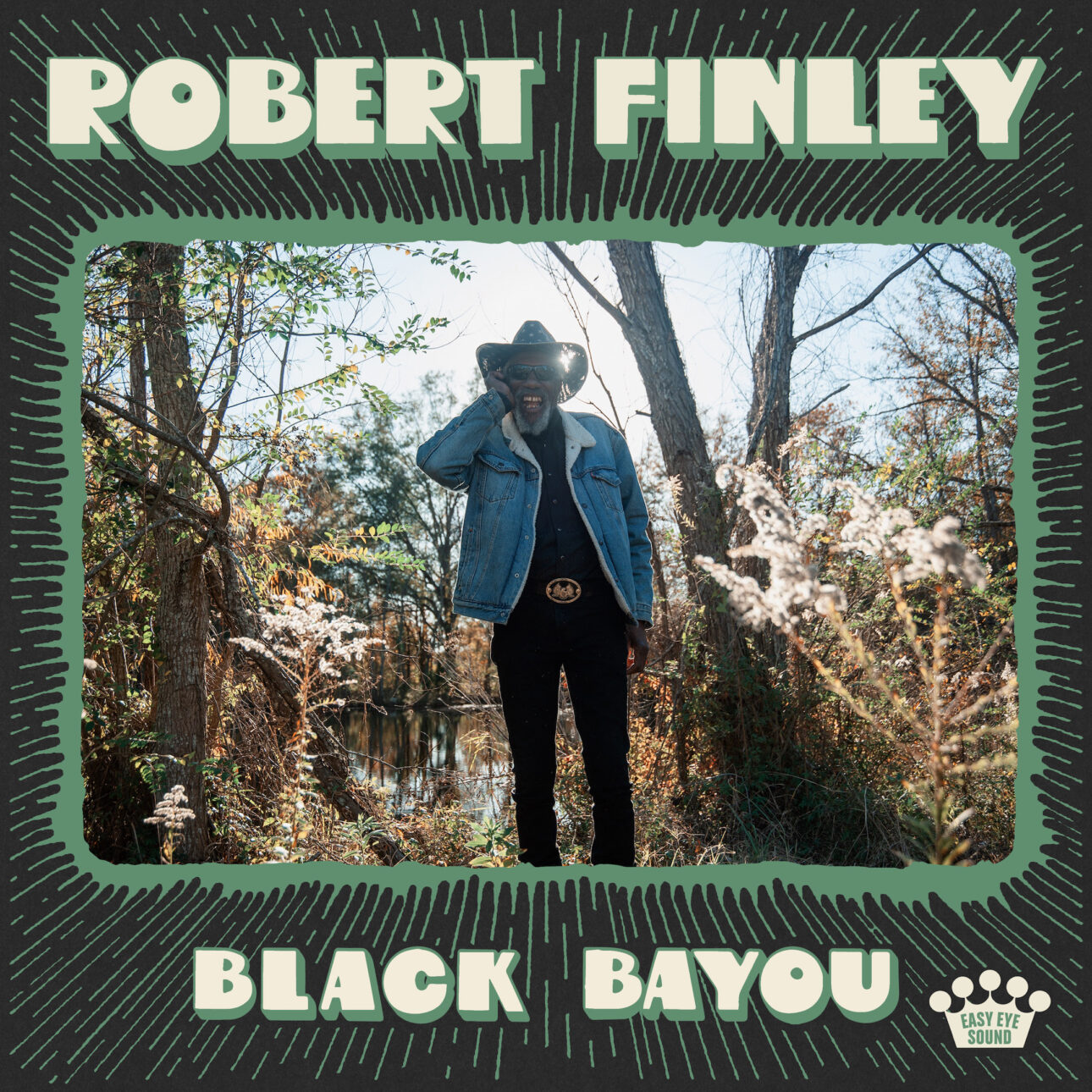

On this mid-October afternoon, he’s excited to finally share his newest album upon its October 27th release. As with Sharecropper’s Son, Black Bayou is produced by Dan Auerbach, their fourth together, its stories reflective of Robert’s Louisiana life now. Black Bayou is definitive Robert Finley—a master musician and entertainer—taking all his bluesy swagger up a notch, a bigger sound with heavier grooves, full confirmation that Robert Finley only gets better with time.

“Everything that I dreamed of or prayed for, it’s coming to pass,” he says. “God knows how many [people] got different beliefs, but if you can get 10,000 people or 20,000 people to dance in the streets together with Grandma and Grandpa, and the kids and the grandkids all dancing to the same music, that’s a miracle. You have not only brought nationalities together and you have brought different races together, but you brought also three generations together.” In Robert’s case, four generations: him, his kids, his grandchildren, and great-grandchildren—his daughter and granddaughter singing background on the album. “If you got a chance to speak to the world, then you need to say something positive,” he says.

Since 2021, Robert’s career has skyrocketed, but much of his life revolves around the same grounding themes of music, family, and faith. For over 30 years, he’s called the tiny Louisiana town of Bernice (a stone’s throw from the Arkansas border) his home, its local church a place where he can share music, family, and faith with his community. “I play for the church, been playing for the same church for 21 years now, and I still play for that church,” he says, stating that “the only reason why I’m having the success that I’m having is because of my faith. I still had to give the credit to the good Lord because it’s a miracle, it is a blessing.” His faith and his involvement with his church is even more important now, because he’s “reaping the harvest. They say you’re going to reap what you sow.”

Black Bayou’s seventh track, “Nobody Wants to Be Lonely,” carries a critical message. “[It] was written for people like that that don’t have nobody they can really depend on,” Robert explains. “Kids drop their parents off at the nursing home. They get the power of attorney, they sell all their stuff, and then they wait for the insurance money. That song was written to be an eye-opener, so maybe some of your kids or grandkids will feel guilty and go see about grandma or go see about grandpa. It’s an eye-opener.

“Even on the song, ‘What Goes Around Comes Around’… Whatever you’re doing, it’s going to come back. I tell the kids all the time, ‘Be careful how you treat the elderly because that’s your final destination. Ain’t but one way for you to keep from getting old, and that’s to die young. Who wants to do that?’”

Not every song has such deep meaning. The last track, “Alligator Bait,” a reimagined tale of a child being used as, you guessed it, bait for an alligator, is a tribute to the lore that exists within families. “That was my version of sitting down talking, listening to my dad and my uncles talk because I never met my grandpa,” Robert says. “They used to laugh about stuff like that. They’re like, I don’t really think he…but they used to hunt alligators and stuff. That was from listening to them. Like I said, I got that little theory that I would make a joke about it because I never, in real-life, met my grandpa.

“Normally…I try to stick to the truth.”

Truth, faith, and family? “I want to nominate you for President, Robert,” I say, quickly recalling Clinton’s ‘92 sax solo on the Arsenio Hall Show and Obama’s bluesy “Sweet Home Chicago” at a White House fundraising event. Maybe a musician is what America needs to soothe the savage beast?

He chuckles. “Somebody got to tell the truth,” he says. “I’m not a politician, so I don’t have to lie to get no vote. I can tell the truth. If they want to hear the truth, the truth would set them free.

“Then reality going to kick in. Then it is what it is.”

He’s afraid that when the new album comes out, he might get kicked out of the church. “They either going to kick me out or they going to promote me in,” he says. Black Bayou’s “Gospel Blues” is for all those “people that try to be holier than everybody else. They going to save the world, but they going to lose their soul because they like to look down on people. Many people, they get a little pat on the back or get a little recognition, all of a sudden, they [think they’re] better than everybody else. They don’t even fool with the people they grew up with no more. They better. They want to build a three-story house and look down out the window on everybody.”

Robert’s message: Stay focused and stay humble. “The same people that voted you in can vote you out. The higher you put yourself up, the further you going to have to fall back down because what goes up must come down.”

For the record, he doesn’t care what society thinks of him, because “they don’t have a heaven or hell to put me in. They can try to send me there. They can tell me to go to hell, but they can’t make me go.” He believes his humility will be his saving grace. “I just want to say I made a difference in this world. At least somebody told the truth, and somebody used their gifts in the right direction.”

Today, the 2019 America’s Got Talent semi-finalist is building a studio on his home property for “young people that got talent.” Aside from fostering young musicians, it’s a place to create both opportunity, as well as community. “Everybody needs everybody,” he says. “The record labels, they need talented artists that’s willing to work and perform. The artists need people to get them the recognition they need. It’s all about working together. I need the record label, and the record label need people like me, just like I need people like them. Then like you, I need people like you that concerned enough to write about my dream and publish it. Then you need people that’s got a dream worth writing about.”

Honesty, a trait traditionally top-rated for both politics and church, is the very same trait that he feels might alienate him from both. If he can’t solve America’s problems, he’ll start with his local church – and get wine back into the challises. “I complained because they took the real wine out and put the grape juice in,” he says. “I’m like, ‘If God didn’t want nobody to drink wine, why would Jesus turn the water into wine?’ He laughs, but he’s quite serious about this, feeling it compromises the parishioners in so many ways. “[Who] wouldn’t get up on Sunday morning, and go to church if he know he going to get a glass of free wine? He might come for the wine, but he might get saved. Anything could happen. A miracle could happen for him while he there.

“There is nothing in the Bible that said you shouldn’t drink, don’t drink. That’s a man -made thing, because he couldn’t handle his liquor. Now Noah got drunk and he saved mankind. After the flood, he got drunk, but he did everything God told him to do. Then he had a drink, he deserved that drink.

“I say crazy things, but they make sense to me.”

Like Noah, Robert built something big and wondrous out of an improbable calling. While he’s grateful for all his success, he still has dreams. Those dreams give him purpose. “If you ever accomplish all your missions, then there’s no purpose. There’s nothing worth living for,” he tells me. “No matter what I accomplish, I try to have something bigger and better and plan to keep my dream alive… I’m grateful for everything that’s happened in my music career, but I’m still a dreamer.”